Governments have been making the same pitch for centuries. We’ll take a little of your liberty, and in return we’ll give you safety. It’s not a new argument. It just has better branding and more antennas now.

Systems like Flock cameras are sold as the latest version of that old bargain. Some privacy loss, we’re told, is the price of modern public safety.

The problem is that the “safety” side of this deal rests on systems built and configured in ways that fall well short of basic security practice.

Security researcher Jon Gaines recently published a detailed technical analysis of the Flock device ecosystem in the whitepaper Examining the Security Posture of an Anti-Crime Ecosystem and the accompanying Distributable Formal Statement. What he documented was not a single clever exploit or a one-off mistake. It was a pattern of design and deployment decisions that leave these surveillance systems easier to access, modify, or misuse than the public has been led to believe.

Not a Glitch, but a Pattern

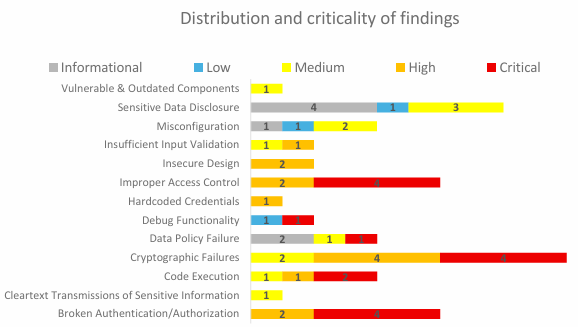

Gaines identified 51 separate security findings across Flock license plate readers, gunshot detection devices, compute boxes, and associated applications. More than twenty of these issues have been assigned CVE identifiers, which are catalog numbers used internationally to track security vulnerabilities in everything from operating systems to critical infrastructure.

The findings point in the same direction. Core protections that are considered standard in modern devices are missing or disabled. Administrative controls are exposed without adequate safeguards. Sensitive data is stored in ways that assume a friendly world where no one with physical access ever acts out of curiosity, malice, or simple mischief.

Surveillance Systems Built Without Basic Safeguards

Flock devices are deployed in public spaces, mounted in ways that allow maintenance and servicing in the field. According to the research, physical access to certain units can allow an attacker to bypass protections, extract stored data, or alter how the device operates.

Some devices were found to ship without Secure Boot enabled, which is the feature that ensures a device only runs trusted software when it starts. Without secure boot, a device cannot reliably verify that its software is still the original code. If it has been altered somewhere along the way, the system has no reliable way to tell the difference.

Other devices store data without encryption, meaning sensitive information is left without one of the most basic forms of protection. That might be brushed off in a novelty gadget. In a surveillance network that tracks people’s movements, it is more difficult to wave away.

Hidden Access and Shared Credentials

One of the more striking findings involves hidden debug or maintenance functionality. Certain devices can be pushed into a maintenance mode through pressing a button three times. In that state, the device exposes a wireless access point protected by a default password that is shared across units and embedded in the firmware.

That is the kind of shortcut you expect in a prototype, not in equipment deployed over entire communities. We are told this surveillance is disciplined and professionally managed. This research shows the professionalism is more marketing than engineering.

Running on Yesterday’s Software

Some Flock license plate readers were found running Android Things 8.1, an operating system that reached end of life years ago. Software in that state no longer receives security updates or ongoing support, which means newly discovered security issues will never be patched.

What This Means in Practice

This is not a story about a single dramatic breach. It is about how these systems were built and what that says about the care behind them. The research documents multiple paths to access or modification, along with technical choices that reveal the system’s security is far more fragile than advertised.

This is not just about privacy. It is about whether the systems collecting this data deserve the level of trust placed in them. Agencies are relying on technology that independent research shows can be accessed or modified through multiple paths. If a device’s logs or files can be quietly altered by anyone with physical access, the digital ‘chain of custody’ is broken. Evidence from these cameras shouldn’t just be untrusted; it should be inadmissible.

The Deal We Were Promised

The public conversation usually frames these systems as a trade. Some loss of privacy in exchange for measurable gains in safety.

What this research suggests is that the trade looks different in practice. More surveillance leads to more data, but that data depends on systems that are not especially hard to tamper with and not especially easy to trust. The promised safety rests on a technical foundation that deserves more scrutiny than it has received.

Banish Big Brother opposes mass surveillance on principle. The GainSec findings add a practical dimension to that position. A surveillance system that can be compromised, manipulated, or quietly abused is not simply a civil liberties concern. It is also a liability for the communities it is supposed to protect.

Print this report. Send it to your city council. Ask them if they are willing to stake their reputation, and your community’s safety, on a system this vulnerable.

Zach Varnell

Zach Varnell is a cybersecurity expert and advocate for privacy and individual liberty. He is a founding member of Banish Big Brother, a nonprofit dedicated to combating invasive surveillance. He also runs Asteros, a security firm that helps software teams and compliance-driven organizations understand and reduce their real-world risk. His insights have been featured in publications like Infosecurity Magazine, Threatpost, ZDNET, and the Washington Examiner.